The cumulative distribution function

Contents

The cumulative distribution function¶

Take a continuous random variable \(X\). The cumulative distribution function (CDF) \(F_X(x)\) gives you the probability that \(X\) is smaller than \(x\), i.e., the definition is:

Notice that the \(X\) is a subscript here. This is because each random variable has its own CDF. Now to save me some typing, I am going to write \(F(x)\) instead of \(F_X(x)\). We only have one random variable anyway.

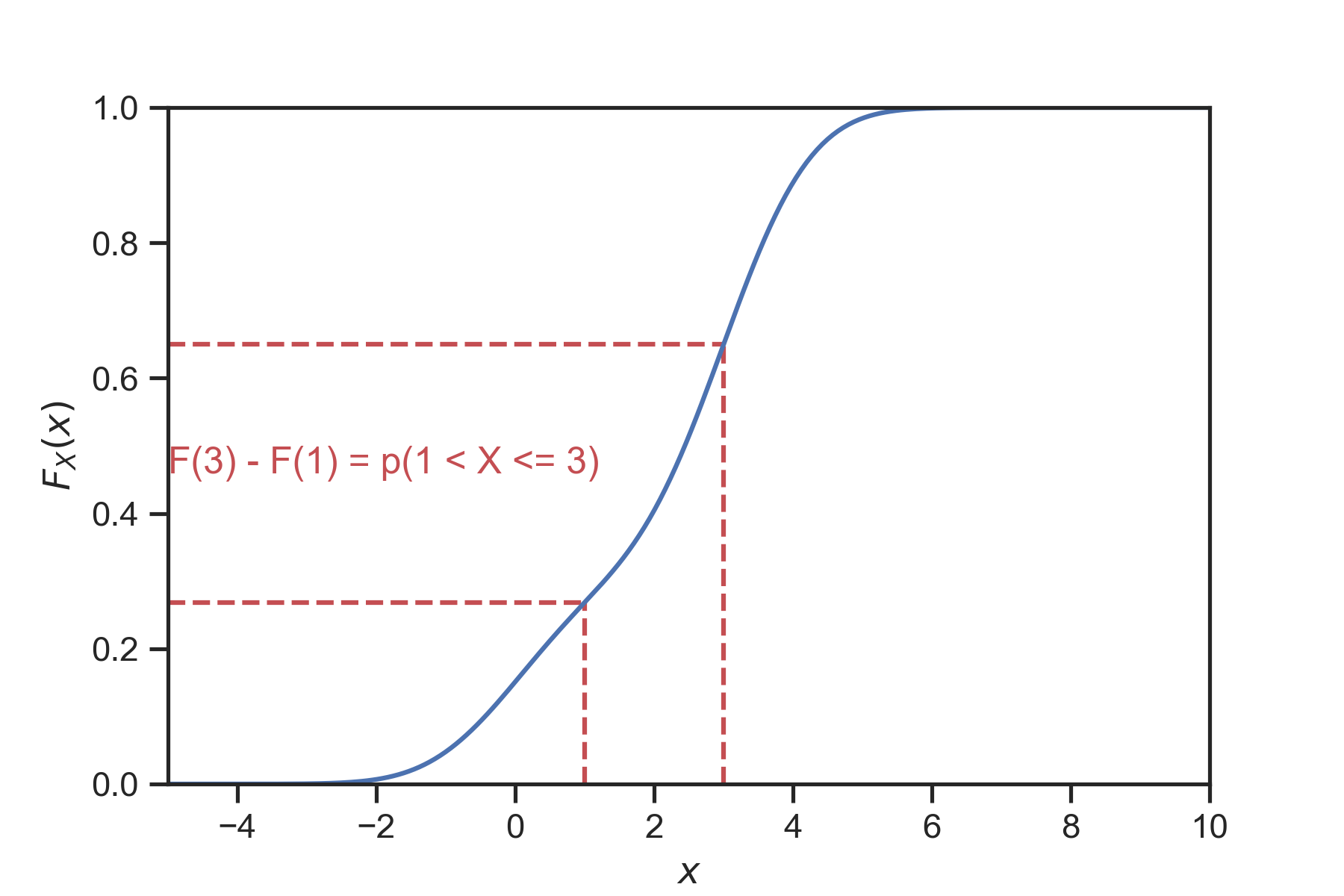

There are certain properties that the CDF satisfies. We visualize the properties in Fig. 7. It is very instructive to go through the proof of these properties. The remarkable thing is that the proofs only use the basic probability rules.

Fig. 7 The CDF of a typical continuous random variable looks like this. It is an increasing function. It converges to zero for very small values. It converges to one for very large values. The probability of the random variable being within a given interval is the difference of CDF values at the endpoints of that interval. In this figure, \(p(1 < X \le 3) = F(3) - F(1)\).¶

CDF property 1: The CDF is an increasing function of \(x\)¶

This property makes a lot of intuitive sense if you think about what the CDF means:

The CDF at \(x\) is the probability that the random variable \(X\) is smaller than \(x\).

If you increase \(x\), then the probability that \(X\) is smaller than \(x\) should increase.

This is pretty much it. But let’s actually prove it rigorously. Take two values \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) such that \(x_1 < x_2\). We need to show that \(F(x_1)\le F(x_2)\). Here it is:

because \(p(x_1 < X \le x_2)\ge 0\). This concludes the proof.

CDF property 2: The CDF goes to zero for very small values¶

Mathematically, this is written as:

Again, this is easy to understand:

The CDF at \(x\) is the probability that the random variable \(X\) is smaller than \(x\).

Make the \(x\) very very small, smaller than any of the values \(X\) can take, and you get zero probability.

CDF property 3: The CDF goes to one for very large values¶

Mathematically, this is written as:

Use your intuition:

The CDF at \(x\) is the probability that the random variable \(X\) is smaller than \(x\).

Make the \(x\) very very large, larger than any of the values \(X\) can take, and you get probability one.

CDF property 4: Probability of values in interval¶

This property says that the probability of the random variable \(X\) taking values inside an interval \([a,b]\) is given by the difference of the values of CDF at \(b\) and \(a\). Mathematically:

This is obviously extremely useful because it tells you how to find any interval probability if you know the CDF. The proof is not that trivial. But it only uses the common rules. Let’s do it:

A corollary of this property is that if \(F(x)\) is a continuous function for all \(x\), then the probability that \(X\) takes exactly a given value is always zero. Here is how you can see this. Take the probability that \(X\) is between \(x\) and \(x + \Delta x\) for some small \(\Delta x\). It is:

Now, take \(\Delta x \rightarrow 0\). The left hand side goes to \(p(X=x)\). The right hand side goes to zero if \(F(x)\) is continuous at \(x\). Thus:

if \(F(x)\) is continuous at \(x\).

All of the continuous random variables we will consider in this class satisfy this property.